1705035175

西南联大英文课(英汉双语版) [:1705033803]

1705035176

7 生活的目的

1705035177

1705035178

在概述了中国的艺术与生活之后,我们不得不承认中国人的确是精通生活艺术的大师。他们全心全意地致力于物质生活,其热忱决不下于西方,并且更为成熟,或许还更为深沉。在中国,精神的价值并未与物质的价值相分离,反而帮助了人们更好地享受自己命定的生活。这就解释了为什么我们具有一种快活的性情和根深蒂固的幽默。一个无宗教信仰的人会对现世的世俗生活抱有一种粗野的热忱,并且融物质与精神两种价值于一身,这在基督徒是难以想象的。我们能够同时生活在感官世界和精神世界之中,而不认为两者一定会有什么冲突。因为人类的精神是被用来美化生活,提炼生活的精华,或许还能帮助生活克服感官世界中不可避免的种种丑恶和痛苦,而不是用来逃避生活,或在来世找寻生活的意义。孔子在回答一位弟子关于死亡的问题时说:“未知生,焉知死?”这句话表达了一种对于生命和知识问题的庸俗、具体而实用的态度,而正是这种态度造就了我们现在国民生活及思维的特征。

1705035179

1705035180

这一立场为我们树立了多层级的价值尺度。这种生活标准适用于知识和人生的方方面面,解释了我们喜好与憎恶某一事物的原因。这种生活标准已经融入我们的民族意识,不需要任何文字上的说明、界定或阐释。我认为也正是这种生活标准促使我们在艺术、人生和文学中本能地怀疑城市文明,而崇尚田园理想;促使我们在理智的时刻厌恶宗教,涉猎佛学但从不完全接受其合乎逻辑的结论;促使我们憎恶机械发明。正是这种对于生活的本能信仰,赋予我们一种坚定的常识,面对生活的万千变化以及智慧的无数棘手问题,可以做到岿然不动。它使我们能够沉着地、完整地看待生活,并维系固有的价值观念。它也教会了我们一些简单的智慧,比如尊敬老人,享受家庭生活的乐趣,接受生活,接受性别差异,接受悲哀。它使我们注重这样几种寻常的美德:忍耐、勤劳、节俭、中庸与和平主义。它使我们不至于发展某些怪异极端的理论,不至于成为自己智慧产品的奴隶。它赋予我们一种价值观,教会我们同时接受生活给予我们的物质和精神财富。它告诉人们:归根结底,只有人类的幸福才是一切知识的最终目标。于是我们得以在命运的浮沉中调整自己,欣欣然生活在这个行星之上。

1705035181

1705035182

我们是一个古老的民族。在老人看来,我们民族的过去以及变化万端的现代生活,有不少是浅薄的,也有不少确实触及了生活的真谛。同任何一个老人一样,我们对进步有所怀疑,我们也有点懒散。我们不喜欢为一只球在球场上争逐,而喜欢漫步于柳堤之上,听听鸟儿的鸣唱和孩子的笑语。生活是如此动荡不安,因而当我们发现了真正令自己满意的东西,我们就会抓住不放,就像一位母亲在黑暗的暴风雨之夜里紧紧搂住怀中的婴孩。我们对探险南极或者攀登喜马拉雅山实在毫无兴趣,一旦西方人这样做,我们会问:“你做这件事的目的何在?你非得到南极去寻找幸福吗?”我们会光顾影院和剧场,然而内心深处却认为,相比荧幕上的幻象,现实生活中儿童的嬉笑同样能给我们带来欢乐和幸福。如此一来,我们便情愿待在家里。我们不认为亲吻自己的老婆必定寡淡无味,而别人的妻子仅仅因为是别人的妻子就显得更加楚楚动人。我们在身处湖心之时并不渴望走到山脚下去,我们在山脚下时也并不企求登至山顶。我们信奉今朝有酒今朝醉,花开堪折直须折。

1705035183

1705035184

人生在很大程度上不过是一场闹剧,有时最好做个超然的旁观者,或许比一味参与要强得多。我们就像一个刚刚醒来的睡梦者一样,看待人生用的是一种清醒的眼光,而不是带着昨夜梦境的浪漫色彩。我们乐于放弃那些捉摸不定、令人向往却又难以达到的东西,同时紧紧抓住不多的几件我们清楚会给自己带来幸福的东西。我们常常喜欢回归自然,以之为美和真正的、深沉的、长久的幸福的永恒源泉。尽管丧失了进步与国力,我们还是能够打开窗子,聆听金蝉的鸣声,欣赏秋天的落叶,呼吸菊花的芬芳。秋月朗照之下,我们感到心满意足。

1705035185

1705035186

我们现在身处民族生活的秋天。在我们生命中的某一时刻,无论是民族还是个人,都为新秋精神所渗透:绿色错落着金色、悲伤交织着欢乐、希望混杂着怀旧。在这一时刻,春天的单纯已成记忆,夏日的繁茂已为空气中微弱回荡着的歌吟。我们看待人生,不是在筹谋怎样发展,而是去考虑如何真正地活着;不是怎样奋发劳作,而是如何珍惜当下的宝贵时光尽情享乐;不是如何挥霍自己的精力,而是养精蓄锐应对冬天的到来。我们感到自己已经到达某个地方,安顿了下来,并找到了自己想要的东西。我们还感到已经获得了某种东西,这与过去的荣华相比尽管微不足道,却像是褪去了夏日繁茂的秋林一样,仍然有些余晖在继续放光。

1705035187

1705035188

我喜欢春天,可它过于稚嫩;我喜欢夏天,可它过于骄矜。因而我最喜欢秋天,喜欢它泛黄的树叶、成熟的格调和斑斓的色彩。它带着些许感伤,也带着死亡的预兆。秋天的金碧辉煌所展示的不是春天的单纯,也不是夏天的伟力,而是接近高迈之年的老成和睿智——明白人生有限因而知足,这种“生也有涯”的感知与丰富的人生经验变幻出和谐的秋色:绿色代表生命和力量,橘黄代表金玉的内容,紫色代表屈从与死亡。在月光照耀下,秋天陷入沉思,露出苍白的神情;而当夕阳的余晖抚摸她面容的时候,她仍然能够爽悦地欢笑。山间的晨风拂过,枝杈间片片颤动着的秋叶舞动着飘向大地,你真不知道这落叶的歌吟是欣喜的欢唱还是离别的泪歌,因为它是新秋精神的歌吟:镇定、智慧、成熟。这种歌吟用微笑面对悲伤,赞颂那种令人振奋、敏锐而冷静的神情——这种秋的精神在辛弃疾的笔下表现得最为恰切:

1705035189

1705035190

少年不识愁滋味,爱上层楼。爱上层楼,为赋新词强说愁。 而今识尽愁滋味,欲说还休。欲说还休,却道天凉好个秋。

1705035191

1705035192

(佚名 译)

1705035193

1705035194

西南联大英文课(英汉双语版) [:1705033804]

1705035195

8 A SACRED MOUNTAIN

1705035196

1705035197

By G. Lowes Dickinson

1705035198

1705035199

1705035200

A SACRED MOUNTAIN, from Appearances: Being Notes of Travel , by G. Lowes Dickinson, published by G. Allen.

1705035201

1705035202

1705035203

1705035204

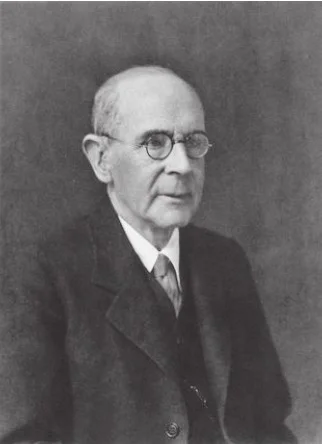

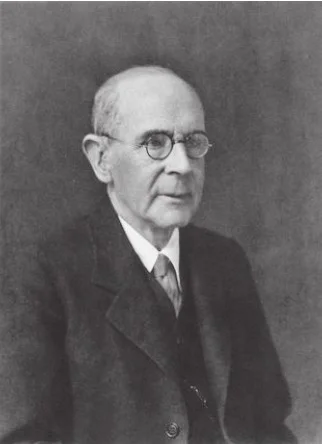

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (1862-1932), English philosopher who spent a lifetime as fellow at King’s College, Cambridge University. Dickinson rose to international fame with his Letters from a Chinese Offcial: Being an Eastern View of Western Civilization (1901). He called himself a socialist in that he was moved by a profound dislike of the existing social disorder, but he looks rather to the past than to the future, to things of the spirit rather than to continued material progress. The views of such a man upon the Orient was certain to be sympathetic and penetrating; sent thither by the trustees of the Albert Kahn Traveling Fellowships, he made a striking brief report upon the spiritual and cultural estates of India, China, and Japan in An Essay on the Civilizations of India, China, and Japan .

1705035205

1705035206

It was midnight when the train set us down at Taianfu. The moon was full. We passed across fields, through deserted alleys where sleepers lay naked on the ground, under a great gate in a great wall, by halls and pavilions, by shimmering, tree-shadowed spaces, up and down steps, and into a court where cypresses grew. We set up our beds in a veranda, and woke to see leaves against the morning sky. We explored the vast temple and its monuments—iron vessels of the T‘ang age, a great tablet of the Sungs, trees said to date from before the Christian era, stones inscribed with drawings of these by the Emperor Chien Lung, hall after hall, court after court, ruinous, overgrown, and the great crumbling walls and gates and towers. Then in the afternoon we began the ascent of Tai Shan, the most sacred mountain in China, the most frequented, perhaps, in the world. There, according to tradition, legendary emperors worshiped God. Confucius climbed it six centuries before Christ, and sighed, we are told, to find his native state so small. The great Chin Shih Huang was there in the third century B. C. Chien Lung in the eighteenth century covered it with inscriptions. And millions of humble pilgrims for thirty centuries at least have toiled up the steep and narrow way. Steep it is, for it makes no detours, but follows straight up the bed of a stream, and the greater part of the five thousand feet is ascended by stone steps. A great ladder of eighteen flights climbs the last ravine, and to see it from below, sinuously mounting the precipitous face to the great arch that leads on to the summit, is enough to daunt the most ardent walker. We at least were glad to be chaired some part of the way. A wonderful way! On the lower slopes it passes from portal to portal, from temple to temple. Meadows shaded with aspen and willow border the stream as it falls from green pool to green pool. Higher up are scattered pines. Else the rocks are bare—bare, but very beautiful, with that significance of form which I have found everywhere in the mountains of China.

1705035207

1705035208

To such beauty the Chinese are peculiarly sensitve. All the way up, the rocks are carved with inscriptions recording the charm and the sanctity of the place. Some of them were written by emperors; many, especially, by Chien Lung, the great patron of art in the eighteenth century. They are models, one is told, of calligraphy as well as of literary composition. Indeed, according to Chinese standards, they could not be the one without the other. The very names of the favorite spots are poems in themselves. One is “the pavilion of the phœnixes”; another “the fountain of the white cranes.” A rock is called “the tower of the quickening spirit”; the gate on the summit is “the portal of the clouds.” More prosaic, but not less charming, is an inscription on a rock in the plain, “the place of the three smiles,” because there some mandarins, meeting to drink and converse, told three peculiarly funny stories. Is not that delightful? It seems so to me. And so peculiarly Chinese!

1705035209

1705035210

It was dark before we reached the summit. We put up in the temple that crowns it, dedicated to Yü Huang, the “Jade Emperor” of the Taoists; and his image and those of his attendant deities watched our slumbers. But we did not sleep till we had seen the moon rise, a great orange disk, straight from the plain, and swiftly mount till she made the river, five thousand feet below, a silver streak in the dim gray levels.

1705035211

1705035212

Next morning, at sunrise, we saw that, north and east, range after range of lower hills stretched to the horizon, while south lay the plain, with half a hundred streams gleaming down to the river from the valleys. Full in view was the hill where, more than a thousand years ago, the great T‘ang poet Li Tai-p‘o retired with five companions to drink and make verses. They are still known to tradition as the “six idlers of the bamboo grove”; and the morning sun, I half thought, still shines upon their symposium. We spent the day on the mountain; and as the hours passed by, more and more it showed itself to be a sacred place. Sacred to what god? No question is harder to answer of any sacred place, for there are as many ideas of the god as there are worshipers. There are temples here to various gods: to the mountain himself; to the Lady of the mountain, Pi Hsia-yüen, who is at once the Venus of Lucretius—“goddess of procreation, gold as the clouds, blue as the sky,” one inscription calls her—and the kindly mother who gives children to women and heals the little ones of their ailments; to the Great Bear; to the Green Emperor, who clothes the trees with leaves; to the Cloud-compeller; to many others. And in all this, is there no room for God? It is a poor imagination that would think so. When men worship the mountain, do they worship a rock, or the spirit of the place, or the spirit that has no place? It is the latter, we may be sure, that some men adored, standing at sunrise on this spot. And the Jade Emperor—is he a mere idol? In the temple where we slept were three inscriptions set up by the Emperor Chien Lung. They run as follows:

1705035213

1705035214

“Without labor, O Lord, Thou bringest forth the greatest things.”

1705035215

1705035216

“Thou leadest Thy company of spirits to guard the whole world.”

1705035217

1705035218

“In the company of Thy spirits Thou art wise as a mighty Lord to achieve great works.”

1705035219

1705035220

These might be sentences from the Psalms; they are as religious as anything Hebraic. And if it be retorted that the mass of the worshipers on Tai Shan are superstitious, so are, and always have been, the mass of worshipers anywhere. Those who rise to religion in any country are few. India, I suspect, is the great exception. But I do not know that they are fewer in China than elsewhere. For that form of religion, indeed, which consists in the worship of natural beauty and what lies behind it—for the religion of a Wordsworth—they seem to be preëminently gifted. The cult of this mountain, and of the many others like it in China, the choice of sites for temples and monasteries, the inscriptions, the little pavilions set up where the view is loveliest—all go to prove this. In England we have lovelier hills, perhaps, than any in China. But where is our sacred mountain? Where, in all the country, the charming mythology which once in Greece and Italy, as now in China, was the outward expression of the love of nature?

1705035221

1705035222

“Great God, I’d rather be

1705035223

1705035224

A pagan suckled in a creed outworn;