1705035194

西南联大英文课(英汉双语版) [:1705033804]

1705035195

8 A SACRED MOUNTAIN

1705035196

1705035197

By G. Lowes Dickinson

1705035198

1705035199

1705035200

A SACRED MOUNTAIN, from Appearances: Being Notes of Travel , by G. Lowes Dickinson, published by G. Allen.

1705035201

1705035202

1705035203

1705035204

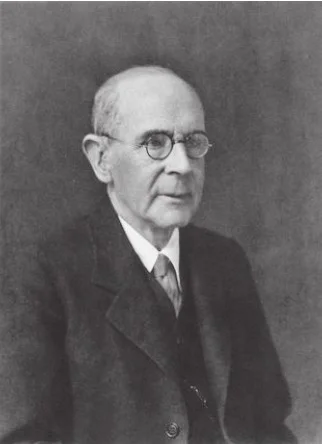

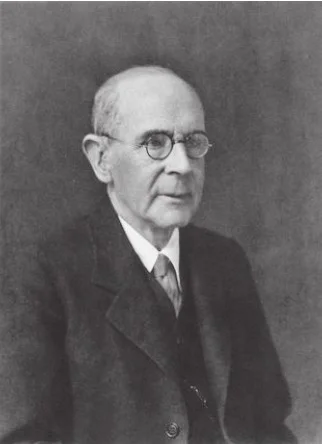

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (1862-1932), English philosopher who spent a lifetime as fellow at King’s College, Cambridge University. Dickinson rose to international fame with his Letters from a Chinese Offcial: Being an Eastern View of Western Civilization (1901). He called himself a socialist in that he was moved by a profound dislike of the existing social disorder, but he looks rather to the past than to the future, to things of the spirit rather than to continued material progress. The views of such a man upon the Orient was certain to be sympathetic and penetrating; sent thither by the trustees of the Albert Kahn Traveling Fellowships, he made a striking brief report upon the spiritual and cultural estates of India, China, and Japan in An Essay on the Civilizations of India, China, and Japan .

1705035205

1705035206

It was midnight when the train set us down at Taianfu. The moon was full. We passed across fields, through deserted alleys where sleepers lay naked on the ground, under a great gate in a great wall, by halls and pavilions, by shimmering, tree-shadowed spaces, up and down steps, and into a court where cypresses grew. We set up our beds in a veranda, and woke to see leaves against the morning sky. We explored the vast temple and its monuments—iron vessels of the T‘ang age, a great tablet of the Sungs, trees said to date from before the Christian era, stones inscribed with drawings of these by the Emperor Chien Lung, hall after hall, court after court, ruinous, overgrown, and the great crumbling walls and gates and towers. Then in the afternoon we began the ascent of Tai Shan, the most sacred mountain in China, the most frequented, perhaps, in the world. There, according to tradition, legendary emperors worshiped God. Confucius climbed it six centuries before Christ, and sighed, we are told, to find his native state so small. The great Chin Shih Huang was there in the third century B. C. Chien Lung in the eighteenth century covered it with inscriptions. And millions of humble pilgrims for thirty centuries at least have toiled up the steep and narrow way. Steep it is, for it makes no detours, but follows straight up the bed of a stream, and the greater part of the five thousand feet is ascended by stone steps. A great ladder of eighteen flights climbs the last ravine, and to see it from below, sinuously mounting the precipitous face to the great arch that leads on to the summit, is enough to daunt the most ardent walker. We at least were glad to be chaired some part of the way. A wonderful way! On the lower slopes it passes from portal to portal, from temple to temple. Meadows shaded with aspen and willow border the stream as it falls from green pool to green pool. Higher up are scattered pines. Else the rocks are bare—bare, but very beautiful, with that significance of form which I have found everywhere in the mountains of China.

1705035207

1705035208

To such beauty the Chinese are peculiarly sensitve. All the way up, the rocks are carved with inscriptions recording the charm and the sanctity of the place. Some of them were written by emperors; many, especially, by Chien Lung, the great patron of art in the eighteenth century. They are models, one is told, of calligraphy as well as of literary composition. Indeed, according to Chinese standards, they could not be the one without the other. The very names of the favorite spots are poems in themselves. One is “the pavilion of the phœnixes”; another “the fountain of the white cranes.” A rock is called “the tower of the quickening spirit”; the gate on the summit is “the portal of the clouds.” More prosaic, but not less charming, is an inscription on a rock in the plain, “the place of the three smiles,” because there some mandarins, meeting to drink and converse, told three peculiarly funny stories. Is not that delightful? It seems so to me. And so peculiarly Chinese!

1705035209

1705035210

It was dark before we reached the summit. We put up in the temple that crowns it, dedicated to Yü Huang, the “Jade Emperor” of the Taoists; and his image and those of his attendant deities watched our slumbers. But we did not sleep till we had seen the moon rise, a great orange disk, straight from the plain, and swiftly mount till she made the river, five thousand feet below, a silver streak in the dim gray levels.

1705035211

1705035212

Next morning, at sunrise, we saw that, north and east, range after range of lower hills stretched to the horizon, while south lay the plain, with half a hundred streams gleaming down to the river from the valleys. Full in view was the hill where, more than a thousand years ago, the great T‘ang poet Li Tai-p‘o retired with five companions to drink and make verses. They are still known to tradition as the “six idlers of the bamboo grove”; and the morning sun, I half thought, still shines upon their symposium. We spent the day on the mountain; and as the hours passed by, more and more it showed itself to be a sacred place. Sacred to what god? No question is harder to answer of any sacred place, for there are as many ideas of the god as there are worshipers. There are temples here to various gods: to the mountain himself; to the Lady of the mountain, Pi Hsia-yüen, who is at once the Venus of Lucretius—“goddess of procreation, gold as the clouds, blue as the sky,” one inscription calls her—and the kindly mother who gives children to women and heals the little ones of their ailments; to the Great Bear; to the Green Emperor, who clothes the trees with leaves; to the Cloud-compeller; to many others. And in all this, is there no room for God? It is a poor imagination that would think so. When men worship the mountain, do they worship a rock, or the spirit of the place, or the spirit that has no place? It is the latter, we may be sure, that some men adored, standing at sunrise on this spot. And the Jade Emperor—is he a mere idol? In the temple where we slept were three inscriptions set up by the Emperor Chien Lung. They run as follows:

1705035213

1705035214

“Without labor, O Lord, Thou bringest forth the greatest things.”

1705035215

1705035216

“Thou leadest Thy company of spirits to guard the whole world.”

1705035217

1705035218

“In the company of Thy spirits Thou art wise as a mighty Lord to achieve great works.”

1705035219

1705035220

These might be sentences from the Psalms; they are as religious as anything Hebraic. And if it be retorted that the mass of the worshipers on Tai Shan are superstitious, so are, and always have been, the mass of worshipers anywhere. Those who rise to religion in any country are few. India, I suspect, is the great exception. But I do not know that they are fewer in China than elsewhere. For that form of religion, indeed, which consists in the worship of natural beauty and what lies behind it—for the religion of a Wordsworth—they seem to be preëminently gifted. The cult of this mountain, and of the many others like it in China, the choice of sites for temples and monasteries, the inscriptions, the little pavilions set up where the view is loveliest—all go to prove this. In England we have lovelier hills, perhaps, than any in China. But where is our sacred mountain? Where, in all the country, the charming mythology which once in Greece and Italy, as now in China, was the outward expression of the love of nature?

1705035221

1705035222

“Great God, I’d rather be

1705035223

1705035224

A pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

1705035225

1705035226

So might I, Standing on this pleasant lea,

1705035227

1705035228

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn.”

1705035229

1705035230

That passionate cry of a poet born into a naked world would never have been wrung from him had he been born in China.

1705035231

1705035232

And that leads me to one closing reflection. When lovers of China—“pro-Chinese,” as they are contemptuously called in the East—assert that China is more civilized than the modern West, even the candid Westerner, who is imperfectly acquainted with the facts, is apt to suspect insincere paradox. Perhaps these few notes on Tai Shan may help to make the matter clearer. A people that can so consecrate a place of natural beauty is a people of fine feeling for the essential values of life. That they should also be dirty, disorganized, corrupt, incompetent, even if it were true—and it is far from being true in any unqualified sense—would be irrelevant to this issue. On a foundation of inadequate material prosperity they reared, centuries ago, the superstructure of a great culture. The West, in rebuilding its foundations, has gone far to destroy the superstructure. Western civilization, wherever it penetrates, brings with it water-taps, sewers, and police;but it brings also an ugliness, an insincerity, a vulgarity never before known to history, unless it be under the Roman Empire. It is terrible to see in China the first wave of this Western flood flinging along the coasts and rivers and railway lines its scrofulous foam of advertisements, of corrugated iron roofs, of vulgar, meaningless architectural form. In China, as in all old civilizations I have seen, all the building harmonizes with and adorns nature. In the West everything now built is a blot. Many men, I know, sincerely think that this destruction of beauty is a small matter, and that only decadent æsthetes would pay any attention to it in a world so much in need of sewers and hospitals. I believe this view to be profoundly mistaken. The ugliness of the West is a symptom of disease of the soul. It implies that the end has been lost sight of in the means. In China the opposite is the case. The end is clear, though the means be inadequate. Consider what the Chinese have done to Tai Shan, and what the West will shortly do, once the stream of Western tourists begins to flow strongly. Where the Chinese have constructed a winding stairway of stone, beautiful from all points of view, Europeans or Americans will run up a funicular railway, a staring scar that will never heal. Where the Chinese have written poems in exquisite calligraphy, they will cover the rocks with advertisements. Where the Chinese have built a series of temples, each so designed and placed so as to be a new beauty in the landscape, they will run up restaurants and hotels like so many scabs on the face of nature. I say with confidence that they will, because they have done it wherever there is any chance of a paying investment. Well, the Chinese need, I agree, our science, our organization, our medicine. But is it affectation to think they may have to pay too high a price for it, and to suggest that in acquiring our material advantages they may lose what we have gone near to lose, that fine and sensitive culture which is one of the forms of spiritual life? The West talks of civilizing China. Would that China could civilize the West!

1705035233

1705035234

Notes

1705035235

1705035236

Taianfu, 泰安府,山东省,a city in Shantung Province, at the foot of Tai Shan(泰山), the sacred mountain.

1705035237

1705035238

alleys, very narrow streets.

1705035239

1705035240

shimmering, trembling, quivering, or faint, diffused light.

1705035241

1705035242

court, or courtyard, a space inclosed by walls or buildings; quadrangle.

1705035243